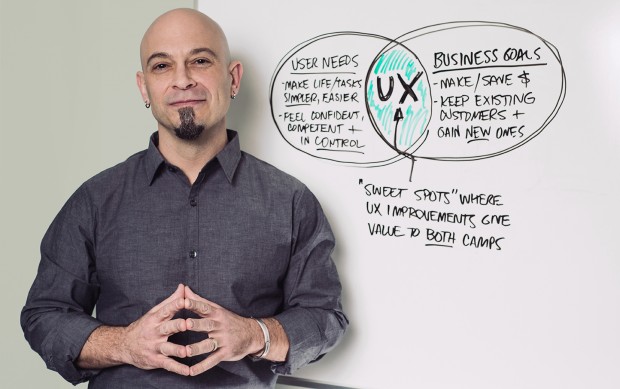

Joe has worked as a UX/CX consultant for nearly three decades. He has had the privilege to work with global organizations from Fortune 100 companies to small startups.

Devoted to help UX students, he has helped over 140,000 students so far. He has written several books and launched eight online courses.

Besides consulting, coaching, writing and teaching he also likes to speak publicly on user experience and design related topics from big global conferences to regional events.

I talked to Joe about the skills UX professionals must have nowadays to succeed in this field. Also, we discussed what parts to include in a UX portfolio and how to stand out from the crowd when applying for a job.

Hi Joe! Thanks for agreeing to this interview. You have been working as a UX consultant for nearly three decades. Could you share some details of your career path? How did you actually become a UX consultant?

Sure, I’ll try to give you the short version. I went to school for Graphic Design, and I was very lucky in that the way I learned design was not just solely about what things look like.

The school I went to — Kent State University in Ohio — taught design as a problem-solving discipline. So it was all about the people on the receiving end. It wasn’t about how it looks, it was about “do people understand what they see? Are they able to act on it? Is it guiding them, helping them, communicating something of value?” So the emphasis was on how people receive what you’re putting in front of them and what they’ll be able to do with it. Which sounds a lot like User Experience, right? It’s the same thing: what are we giving people, what can they do with it, how is it helping them, and does it matter? Is it valuable, does it add value, or is it just decoration, does it just look pretty? So I was lucky that this is the way I was taught design, and that was hammered by our professors.

I started out working in traditional design agencies and was working for a large advertising firm when this little thing called “the Internet” came about. And I could not convince the old guys who ran this agency that this ‘World Wide Web’ thing was important, that it was something they should start paying attention to.

I was young, I was a bit naive and probably a bit brash in feeling like “well, if these guys won’t do it, then I’ll do it myself.” So I jumped ship, took one employee with me, and started my own company to design for the Web. With some help from my good friend and mentor Brian McIntyre, who never gets enough credit for this, I started Natoli Design Group and called it an “Experience Design” firm. We dove headfirst into all things Internet, which was all completely new at the time. We were lucky in terms of timing, because there were no experts, no one knew what they were doing! So it was easy to walk into prospective clients and get work and have them trust us, because we were on an even playing field with everyone else. I and everyone who worked for me learned on the fly, from people like Alan and Sue Cooper, Don Norman, Roger Black, Jesse James Garrett.

So I did that for about 10 years, we grew to 6 employees, small shop, and I sold that company to an IT firm, at a point where I was burned out trying to consult, design and run a business. I hung out there for a few years trying to help them establish a UX practice, but the culture was a bad fit. So I was reminded why I liked working for myself so much, and went back to doing that as an independent consultant.

And that’s what I love. Everything I do, whether it’s for students, for clients, speaking gigs…it’s all teaching. It’s all helping people do what they do easier, more efficiently, and hopefully with a lot less pain and stress. And advising UXers and Designers of all ages and experience levels on what it takes to have a successful career, which a portfolio is a huge part of, is the same thing to me. Teaching, helping.

Sounds great! What do you think what skills someone must have to become a successful UX Consultant or to work at a great company as a UX professional?

I think the most important skill that you have as somebody in design or UX or product development is a willingness to ask questions. The ability to operate from a place where you feel like, “I don’t have all the answers, I’m not going to pretend I have all the answers. My job is to ask questions. My job is to get to the truth, and the reality of what’s happening here.”

And I say that because if you do anything for as long as I have, you see certain patterns. I’ve learned over time that, when there’s a UX problem in a piece of software, in an app, in a website, very rarely does that result from people not having the right skills, or the ability to do good design work or good development work.

That’s rarely the problem. The problem is usually in how that work is being done. There are obstacles and barriers and it all relates back to how people work with each other. So, it’s not enough to say, “Well, the user interface is suffering here, it’s not what it should be.”

Part of what you need to figure out is why did that happen? Why did all these good ideas that were proposed three months ago never make it to the build? Why is the backlog of UX improvements eight miles long? Why can’t we get to this stuff?

So that’s a lot of what I focus on, and I think if you don’t ask those deeper questions, as a UXer or as a consultant, as a designer, you only solve a surface problem. You improve the interface. Which means you treat symptoms instead of underlying causes.

So the next time around, when the team runs sprints to deliver a new update, those improvements never make it to the build then either — because you still have the same problems. You still have the same roadblocks. Even if people know how to make things better, the right questions are, “Why isn’t that happening? Why isn’t it making it to the release? Why doesn’t it show up in the build?”

“You have to set your ego aside and be willing to learn, to find out things that maybe you didn’t expect, to look in areas you didn’t expect to look in.”

You have to be relentlessly curious and not be satisfied with what you see at first, or even what you think is the actual problem. You almost always have to dig a little bit deeper, and you have to be willing to be wrong as well. You have to set your ego aside and be willing to learn, to find out things that maybe you didn’t expect, to look in areas you didn’t expect to look in.

I see. And how do you suggest one showcase these skills in a portfolio? You just mentioned some soft skills that might be harder to showcase than some hard skills.

Well, yes and no. The biggest problem I see in UX and design portfolios is that people don’t tell the stories of HOW they got to the solutions that they’re showing. Too many portfolios are essentially glorified art galleries: “here’s all this really great looking user interface work.”

“The biggest problem I see in UX and design portfolios is that people don’t tell the stories of HOW they got to the solutions that they’re showing.”

If you go to sites like Dribbble or Behance, which a lot of people use as portfolios, or even if you look at individual portfolio websites, you see a lot of visuals. A lot of images of finished UI design, or images of wireframes without any context as to why all that visual design is the right solution, why that font is the right font, why that workflow is the right workflow.

You’ve got to tell the story behind why these were the right decisions. You’ve got to tell the story behind what problems this work solved. You’ve got to tell the story behind what the goal was in the first place. What were you trying to achieve? What was the client trying achieve? What were they hoping to have happen after this launch?

“You’ve got to tell the story behind why these were the right decisions. You’ve got to tell the story behind what problems this work solved.”

So, all the stuff I just talked about can certainly show up in a portfolio, simply by how you frame context around your work, what you say. If I come to your home screen, and it’s just a big image or a big flat field, or a picture of your face, and it says, “Hi, I’m Joe! I’m a UX designer. I love making great experiences.” That doesn’t tell me anything about your ability, about your experience, about what you’ve done, who you’ve done it for, about what makes you unique.

The question a recruiter, or an employer, or even a potential client is asking from the word go is, “Why YOU? Why should I hire YOU? There are 80,000 other people out there looking for jobs.” And that’s true, there are more UX folks looking for jobs right now then there’s ever been. There is also an equally large expansion of available UX jobs.

But when they look at your portfolio, everybody’s asking, “OK, why you? I have 40 other portfolios to look at in the next hour and a half. Why YOU?” And that has to come through quickly.

So the way you do all this in your portfolio, you tell those stories. You make sure that every sentence, even from your introductory headline, delivers something of value, that you’re speaking to something meaningful to somebody on the receiving end.

And then, what would you write on the front page of a portfolio to make sure to stand out?

I think if you have a sentence to work with, you’ve got an opportunity to tell that story. So instead of, “Hi I’m Joe! I love design,” you say, “Hi I’m Joe! I’ve been helping companies make or save money with their products by improving UX for the last 27 years.”

You told me a couple things there. You’ve told me that you’ve been doing this for a long time, that you’ve helped companies make a meaningful difference. You’ve helped them make or save money. That’s a real thing. That’s a thing that companies care about. You’ve told me two valuable pieces of information that I – as an employer, as a recruiter, as a potential client – care about. You’re speaking MY language now instead of yours.

So there’s lots of ways to do that, but you’ve got to give me some sense — really quickly — why you’re the right person for this job. If you specialize in a certain area, let’s say all you do is mobile app improvement to help companies. Then maybe you say something like “successfully monetized mobile apps for the last 10 years” or “I’ve worked with some of the biggest clients in the world doing mobile app improvements’.

In other words, tell me something beyond what your personal passion is. As an employer, as a recruiter, as a client, I don’t care what you love. I’m looking at your portfolio purely for the perspective of “How’s this person going to help me achieve what I already want?” That’s what that first sentence needs to speak to.

You mentioned the importance of adding design stories, basically, to tell the story behind the final design. Does this include showing the design process and the design decisions?

Yes, absolutely. There’s almost always a good story to be told there. And the thing about your product, and the reason I was interested in UXfolio in the first place, is because it’s the only product I have seen so far that does an incredible job of helping people tell those stories easily.

“And the thing about your product, and the reason I was interested in UXfolio in the first place, is because it’s the only product I have seen so far that does an incredible job of helping people tell those stories easily.”

From the format itself, from the fact that it’s really, really easy to add narrative to images and tell a that narrative from start to finish. But UXfolio also includes these templates that say, “OK you need a case study. That looks like this.” “You need this process flow, etc. Great, here’s a way to simply get that done.” To tell those stories as, “OK. this was the goal. Here’s what we were trying to achieve. Here’s how we did it, and here’s why we took these steps”. The tool has to work with you to enable you to tell that story, and you do an excellent job of that.

I don’t mean to pick on Dribbble, but I’m going to, I guess. If you go to Dribbble, if you go to Behance, if you go to Pinterest or Instagram, the best you can do is post an image with a little bit of story behind it. But the two things are not interwoven.

There’s no process. I can’t step through. “OK, here’s what we were after. Here’s what we did. Then we did this. Here’s the result. Then we did this. Here’s the result, and so on.” It doesn’t tell the story.

And as a reader, the ability to do that in chunks is really important to allow people to get through it in the first place. Because if they go to your page, and it’s just a ton of text and one image, people will tune out. They’ll say to themselves, “I’m not reading all that.”

So I find the ability to tell that story, to tell that narrative in chunks — where you can show the work that you’re talking about as you talk about it — tremendously important.

You mentioned narrative. What format or structure would you recommend to use to do this?

I believe in the inverted triangle model of content for web, for software, for apps.

When you learn writing in school, you’re taught to set up a premise. Then you walk through the story. Then you have a conclusion at the end: “Here’s what happened. Here’s what all that means.”

With portfolios, with websites, with apps, with software, you have to do the opposite. You need to lead with the conclusion, the outcome. In other words, you need to start with “here’s what the work I did achieved; here is the result.” Then “here’s the client, here’s what we were trying to do, here’s what happened,” really, really quickly. Then you go into the story of how you got there, how you achieved it, what work you did.

“Your goal with your portfolio, with every single screen, is to keep people from leaving.”

But you have to start with something important enough to the viewer that’s going to keep them looking. Your goal with your portfolio, with every single screen, is to keep people from leaving. So you’ve got to give them something immediately as to why they should read this case study, especially if it happens to be lengthy.

When I check a portfolio I can say, “OK, looks like good work.” I can see that in three seconds. I can look at a UI design and think “OK, that looks pretty good.” But the only reason I care, the only reason I’ll stick around longer than three seconds, is if you tell me you accomplished something that sets off a light bulb in my head that says, “WOW, that’s pretty impressive.”

“Say “200% increase in checkout through the e-commerce process”. Now you’ve got my attention.”

Say “200% increase in checkout through the e-commerce process”. Now you’ve got my attention. For at least the next sixty seconds, I’m going to read some of what you wrote. Because I’m thinking, “Wow! This person accomplished that. That’s pretty impressive. I should check this out.”

You’re always trying to prove that the next couple minutes of that person’s time are well spent. That’s your job, to convince them to stick around and keep reading.

Do you remember a specific example of a very good portfolio? If yes, how did it look?

Off the top of my head: no. But, in my portfolio course “Build a Powerful UX Portfolio” I show examples of portfolios that I think are doing a good job.

I’ve looked at hundreds of portfolios in my life. The thing that spawned that class is I was helping a client staff their department. I looked at over 200 portfolios, which was exhausting. Because I honestly didn’t see one portfolio out of that 200 that was really what I thought it should have been. They all pretty much followed the same format: “Hi I’m Joe. Look at my stuff.” So even the ones that did a good job in some places didn’t really fully tell the story in others.

And I don’t blame anybody for that. I think they’ve gotten bad advice for the most part about what a portfolio is, what it should be, what it should look like, what should go in it.

What mistakes did you see in many design portfolios?

One thing I see a lot of is that on the home screen, everyone looks the same – a big blank color or big image text, “Hi I’m so-and-so.” Everybody takes that format on their front page. Again, you have to be unique, distinct. You have to set yourself apart from the other 8,000 people using the exact same format.

Number one, you’ve got to do something different.

Number two, the thing that I see most often with UXers in particular, is that they’re just presenting heavy visuals.

And here’s the problem with that. If you’re a UX consultant, analyst, strategist, designer, whatever you want to call it… If your work is strategic in nature — which UX is — and you’re just showing images of finished UI, no matter what you say in the text, the message that sends is, “I am a visual designer. I make things look pretty.”

That’s what you’re telling the person looking at it. So no matter what you say or how you present yourself, if you get offered a gig, it’ll be a visual design gig. It’s going to be, “You’re an order taker. I need you to make this look pretty. It’s already designed, it’s already built, we already made all the decisions. I just need you to pretty it up.” That’s who you’re going to be.

“You have to lead with a strategic outcome and communicate that you focused on helping this business do something that matters to them. That’s the only way you’ll be seen as a strategic asset.”

You have to lead with a strategic outcome and communicate that you focused on helping this business do something that matters to them. That’s the only way you’ll be seen as a strategic asset.

My last two questions would be about juniors and seniors. What would you recommend to junior UXers if they do want to get a job but don’t really have anything to show yet? It’s like a circle they can’t get out of. What should they do?

There are multiple ways to do that. You have to find projects. You have to create them. That could be your friend, a musician trying to get his music out into the world. Say, “Hey, I’d like to redesign your website.” And treat it like a UX project: what’s he trying to accomplish? What do we need to communicate? Do wireframes. Do the actual UI design, and tell the story of doing that work.

It could be a small, local business that you go to all the time. You go to their website and you think, “Wow, that’s really crappy!” So you go to them and say, “Look, I’m young. I’m inexperienced, I’d really like to redesign this website. I think it could be better for your business. If you give me free coffee for six months, I’ll redesign it.”

Or you go to a non-profit, a charity organization. A lot of times they don’t have any money to begin with. And it’s important for them, because they’re putting out a good thing in the world. They’re doing good things for people. So you help them, you say, “Let me redesign this for you, I think it could be better.” And again, use that as a way to tell your story.

Or, you take an established product, an established website, an established whatever out there and you redesign and say, “I think this could be improved and here’s why.” Or take an app on your phone where you think, “OK, half of this is good and half of it drives me insane.”

Detail why that is, redesign the parts that drive you insane, and tell that story. You don’t need anybody’s permission to do that. What’s important, what people need to see, is how you think, how you work through problems.

“I think whether or not you have any practical, real world, on-the-job experience, is irrelevant. There’s a way to do something and tell a story.”

So I think whether or not you have any practical, real world, on-the-job experience, is irrelevant. There’s a way to do something and tell a story. It can be done and it should be done. Is it easy? No. Can you do it? Yeah.

Nice! And what would you suggest to seniors? How can they stand out from the crowd of juniors?

It’s interesting. I’ve talked to plenty of people who have said to me, “I’ve been in graphic design for 20 years and I’m just now getting into digital design or UI design or UX work. And I don’t have any UX stories to tell. My past work is all design.”

Or I get people who are excellent front end developers and they say, “I’ve been doing front end development work – coding – for the last 20 years of my life. And now I’m getting into UX, I really love it. I enjoy it. I find that it’s valuable to people. What do I do? I don’t have any UX stories to tell.”

I say to both groups, “You absolutely have UX stories to tell.” Remember what I said about how I learned design? And how it was taught as a problem solving discipline?

Revisit all the work you have ever done. Go back to every website you’ve built. Go back to every print design you’ve created, and you find a way to tell that story in a different way from an UX perspective. “Here’s what we were trying to achieve. Here’s what we wanted people to get from it. Here’s what actually happened. Here’s how it improved people’s ease of use or effectiveness or accuracy or it made or saved the business money. Here’s why it was a successful advertising campaign.”

I don’t care what it is. There’s a user experience story to tell in every single project. All you have to do is go back and look at what you did and think a little differently about it. Same work, but you’re telling the story in a different way, from a different perspective. So that’s entirely possible.

You have to leverage your experience no matter what it is. You don’t have to start fresh if you’re a senior person. You don’t fresh and say, “Well I’ve been doing UX for a year.” Not true. Even if you didn’t call it UX, you were doing UX work. Consciously or not, anytime you design a product, you’re doing UX, intentionally or otherwise.

And if someone really worked (intentionally) as a UX professional for years, what other things can they do to make sure to stand out?

Well it’s kind of the same thing. You have to tell those stories in the context of your experience. Because older designers or older UXers in particular, are concerned about ageism, right? They’re getting older and people are like, “Well, you’re old.”

You’ve got to talk about the benefit of that experience, of being old. And the benefit is, if you’ve been doing something for 20 years, or 27 years or whatever, you’ve seen a lot. You’ve got a lot of time over the target.

What happens over time, for as long as I’ve been doing this, is that you see a lot of the same scenarios, same situations, same stories. It begins to feel like a movie you’ve seen a hundred times. You know the dialogue. You know the plot. You know what’s going to happen next. You know what people are gonna say in reaction to things. It feels like, “I’ve seen this movie before, and I know how it ends.”

That doesn’t result from being the smartest person in the room. It’s the result of a lot of time over the target, a lot of time spent doing something. So if you’re older and you’ve been doing this for a while, that’s to your benefit.

Your storyline to people looking to hire you should be, “I’ve got a lot of experience with what works and what doesn’t. I’ve seen a lot of things succeed and I’ve seen a lot of things fail. And there are commonalities in both those areas. So my strength is, I’ve gotten pretty good at recognizing where things are failing and why, and I can get to the real issue a lot quicker than I would have 15 years ago when I was just starting.”

So again, there’s a story to tell. Your experience is valuable; it matters a lot. But again, it’s how you tell the story. If you present yourself as “outdated person who isn’t really saying anything about how long they’ve been doing this, or how it’s helped organizations,” your age and experience don’t matter anymore. You’ve got to tell a story, a compelling story. A story that matters to the person reading it.

Sure, I see. Do you have anything that you would like to add?

You know, when I had my own company, we had a big whiteboard in a room where instead of having meeting tables, I always had couches. So when clients came in, it was just a comfortable conversation, as opposed to a stiff us-versus-them meeting scenario where people are sitting across from each other at a table. It changes everything.

Anyway, on that whiteboard in the top left corner, and it stayed there for years, this was my advice to my employees, to our designers, to our developers, to everybody. In red ink, all caps: “TELL A COMPELLING STORY.” And that stayed. It was up there and I never erased it. I wanted it to live there.

And that’s what this is about. Your story has to matter to somebody other than you.

“Tell a compelling story. […] That’s what this is about. Your story has to matter to somebody other than you.”

Thank you very much for your time and for all your great advice. I’m sure our readers found it really useful.

Take Joe’s advice, tell a compelling story in your UX portfolio and stand out from the crowd.

As Joe recommended, you can use UXfolio to get help with telling your stories easily. It’s a tool which supports UX professionals with portfolio building.

Using UXfolio, you will get tons of help not only with showcasing your design process and decisions but also with the copywriting part and many more. You can even ask for detailed reviews on your case studies to get the most out of them before applying for your next job.

Tell a compelling story in your UX portfolio with UXfolio:

Click here to sign up and try it out!